Whichever corners of photography internet you lurk in, existential anxieties about implications of artificial intelligence (AI) have likely graced your screen. Its threat is undeniable: AI-generated imagery is becoming so hard to distinguish, it won a world photography award.

Even AI warns we may soon be jobless, thanks to—you guessed it—AI.

Focused on concerns, discussions overlook an underappreciated potential: how AI could revolutionise accessibility for disabled photojournalists and audiences. But as with any transformative technology, this potential is constrained by ethical issues.

The Struggle is Real

For the 1 in 6 of us who are disabled, accessibility means inclusion. Yet photojournalism is often inaccessible: non-adjustable camera interfaces, editing software without accessibility functions, locations unaccommodating to mobility or sensory needs. Oh, and don’t forget the constant ableist microaggressions:

Video: Disability advocate Tiffany Yu highlights the ableist microaggressions disabled people frequently experience. Video by Tiffany Yu.

It all adds up. Structural ableism—physical, systemic, and cultural barriers disadvantaging disabled people—is socially entrenched, and why we make up less than 1% of the media industry.

It’s not much better for audiences. Alternative text? Often considered optional. Social media hashtags? Usually not optimised for screen readers. News outlet and photographers’ websites? Don't always meet accessible design standards.

Imagining AI-ccessibility

AI offers hope, because it can help us address some accessibility issues.

Voice-controlled cameras for photojournalists with mobility issues. Graphics software with responsive auditory feedback for visually impaired editors. AI drones enabling remote shooting, reducing sensory overload for neurodivergent photographers. The technologies exist—we just need to apply them to photojournalism.

Of course, being a photojournalist isn’t just about gear. AI accessibility mapping could scan locations, pinpointing features like ramps, restrooms, and sensory-friendly zones. Insights about potential barriers and solutions could help us plan and execute shoots, with adaptive navigation assistance providing auditory or tactile guidance in the field:

Video: AI-based tools—like augmented navigation app Soundscape, which provides users with auditory cues about their environment—could help make photojournalism more accessible for disabled photographers. Video by Microsoft.

And then there are our viewers. If a photo can say a thousand words, what happens if those words aren’t fully accessible to nearly a fifth of our community? AI could help streamline solutions.

Hashtags could automatically convert to #CamelCase to improve accessibility for screen readers. Interfaces could adapt to user needs, not ‘universal’ design principles that research shows are—in reality—not truly universal.

‘Optional’ alternative text could be automated, or even enhanced through rich audio narratives. Customisable interpretation features could offer information about photographs’ context, history, meaning, or emotion, which can be particularly helpful for cognitively, neurodevelopmentally, or visually disabled viewers:

Original image description: ‘I’m kneeling on the greenhouse floor, gently touching long, skinny leaves that end in sharp tips. Rows of these short plants extend throughout the greenhouse, many of which have dark, still developing pineapples. Mylo is patiently watching me, and the back of his furry head is visible on the bottom left of the photo.’

Image: Deafblind human rights lawyer Haben Girma adds rich descriptions to images—including terms conveying emotional qualities, like ‘gently’ and ‘patiently’—to craft illustrative narratives for viewers. Image and original image description by Haben Girma.

Obviously, these technologies don’t address underlying causes of ableism. But AI-based solutions don’t have to fix everything. They can serve as additional tools to help us build bridges between an inaccessible world and a disabled community deserving of equitable access.

But… (why is there always a but?)

Still, there are problems with AI we have to address if the photojournalism industry is to balance accessibility improvement with ethical responsibility.

AI models are built on content used without permission, raising serious questions about legal and ethical boundaries we are willing to cross. Advancing accessibility shouldn't neglect our rights to consent, compensation, and credit as artists.

As they’re built on human data, AI models also reflect human prejudices. “Racism, sexism and ableism are systemic problems that are baked into our technological systems because they’re baked into society,” explains AI research director Meredith Broussard. Bias in, bias out:

Podcast: While AI is perceived as impartial, it is built on human knowledge and therefore replicates—and sometimes exacerbates—social biases. Podcast by Dr Susan Carland.

Perpetuating discrimination in resources like alternative text or augmented navigation tools consequently risks amplifying some problems while addressing others.

AI, after all, doesn’t have human understanding of sociopolitical dynamics, context, emotion—or ethics.

As such, while AI can identify image content, it doesn’t always discern it accurately, fairly, or with contextualised nuance. Disability rights advocate Alex Haagaard’s series ‘Shitty Alt Text,’ which showcases autogenerated descriptions of iconic images, highlights AI’s limitations:

Image: Instagram AI’s alternative text for Andy Warhol's 1962 ‘Marilyn Diptych’—a silkscreen of 50 repeated photographs of actress Marilyn Monroe—highlights how AI-generated descriptions can lack accuracy and context. Image by Alex Haagaard.

Haagaard's work validates concerns about trusting AI without human oversight. Nevertheless, AI threatens human jobs in the photojournalism industry: roles like alternative text writing, image editing, and accessible interface design are at risk in an AI-automated landscape.

We must therefore be wary of over-relying on AI as a remedy to photojournalistic inaccessibility. Despite offering tools, AI use will generate new problems.

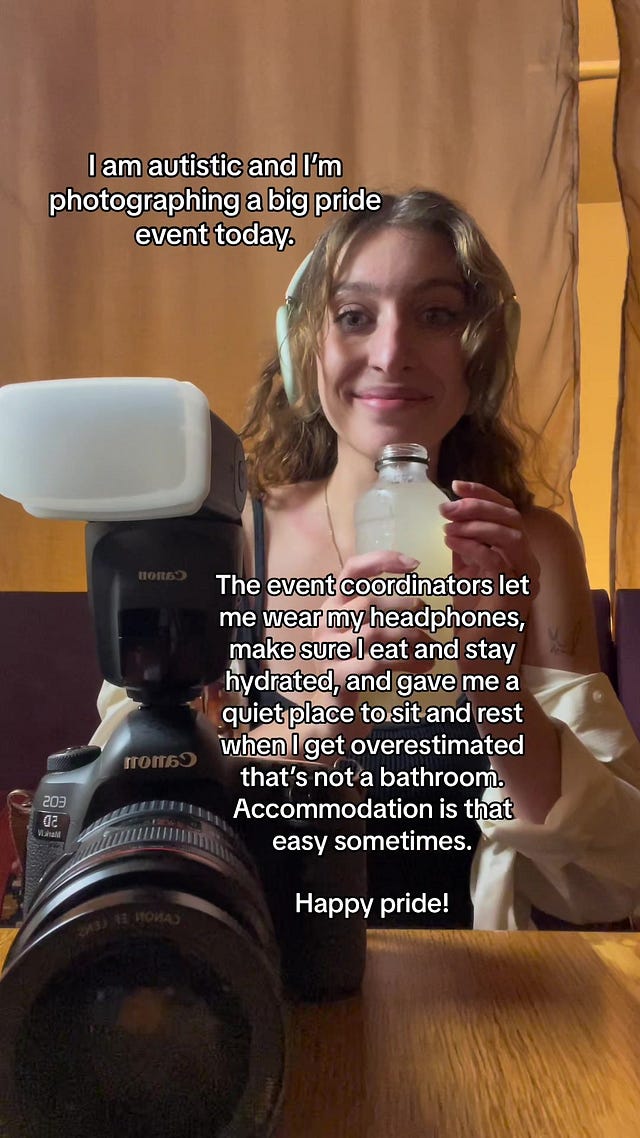

Depending on emerging technologies also can’t overshadow that true accessibility lies in dismantling ableism via human-centred actions, like those experienced by autistic photographer Lexi Brown:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Video: While AI might improve accessibility, event organisers’ accommodations for photographer Lexi Brown highlight the essential role of social actions in combatting structural ableism. Video by Lexi Brown.

An (A)-eye to the future

Past industry developments—like transitions from film to digital, print to online—were met with similar hesitations. Photojournalism’s death has been proclaimed before. But each time, the industry evolved, assimilating the new.

AI in photojournalism is a threat, but also an opportunity: for accessibility, for better inclusion. Using it doesn’t have to just be about easier, automated standards compliance. AI can help foster new ways of engagement, welcoming everyone to the photojournalism table.

Yet, as Alexa Heinrich from Accessible Social argues, accessibility shouldn’t be an afterthought. Let’s champion it as a guiding principle as we begin working with AI.

But let’s do so ethically.