Trigger warning: this article contains discussions of war, violence, colonisation, racism, and death.

In late October, at the Rafah border crossing between Egypt and Gaza, Egyptian podcaster Rahma Zein confronted CNN correspondent Clarissa Ward about western media’s coverage of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“We are watching the results of your silence, of your misrepresentation of Arabs, of your dehumanisation of Arabs,” she said, in a video shared worldwide. “Where are our voices?”

Video: Egyptian podcaster Rahma Zein confronts CNN correspondent Clarissa Ward, highlighting issues related to media representations that lack the voices of those depicted. Video by African Stream.

Rahma’s words highlight a critical issue in visual journalism: the outsider gaze that dominates war photography. Dynamics of power and representation are deeply embedded in photojournalistic practice. Capturing history isn’t just an act of documentation, but also of influence—with images and stories shaping who is represented, misrepresented, or omitted.

Behind the Lens of the ‘Gaze’

Sociologically, this dynamic is called the colonial gaze or white gaze, depending on the context.

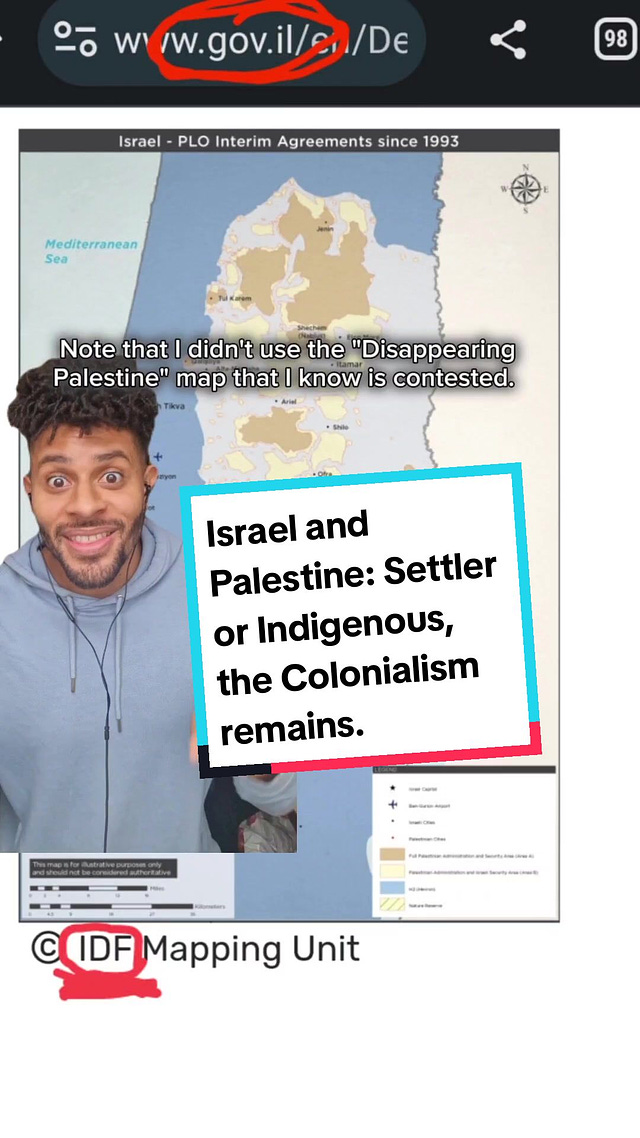

To colonise is to occupy land, but also involves enforcing cultural norms and beliefs through violence, oppression, and erasure. Settler aggression is disproportionately weaponised by white people against First Nations communities and People of Colour, including Palestinians.

Video: Anti-racism Trainer Joris Lechene explains the dynamics of colonisation in the context of Israel and Palestine, highlighting considerations beyond indigeneity. Video by Joris Explains.

Historically, photography has long been used as a colonialist tool, with a well-documented role in reinforcing imperial, white-centric, and racist narratives.

The colonial gaze in photography is a metaphorical lens that frames people and events how the outsider perceives or wants to represent them. Based on an imbalance of power between the observer and observed, the photojournalistic gaze is an act of objectification.

The Gaze in Today’s War Photojournalism

The colonial gaze is not a relic of the past: it actively shapes current media practices. In wars, we see it in ‘helicopter journalism,’ where international outlets send foreign correspondents instead of hiring local reporters.

But correspondents’ hunt for an iconic image or story to feed the incessant demand for fresh blood and trauma in the 24/7 digital media landscape often overlooks local perspectives.

“International media doesn’t trust local sources,” Gaza-based journalist Maram Humaid said in an interview with The Nation, “Not even local journalists. They’d rather send a clueless blond journalist.” As a result, she argues, “there’s a particular narrative about us, read and reproduced by Western journalists, which shapes analysis around Gaza.”

Video: In a Sky News interview, Palestinian journalist Yara Eid joins a chorus of voices in calling out biases in media coverage of the Israeli-Palestinian war. Video by Yara Eid.

In confronting biases in war media informed by the colonial gaze, Rahma, Maram, and Yara highlight that the problem is not just misrepresentation, but the silencing of voices. The stories that are not told, and perspectives that are minimised, create an incomplete narrative. This misleads viewers and strips dignity and agency from those depicted.

Why The Photojournalistic Gaze Matters

The implications of this skewed gaze are significant, as photojournalism shapes responses to global conflicts and crises.

Nick Ut’s photo of 9-year-old Phan Thị Kim Phúc covered in napalm helped turn public opinion against the Vietnam War. David Jackson’s picture of Emmett Till’s mutilated body catalysed America’s bourgeoning civil rights movement. And Nilüfer Demir’s image of drowned Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi impacted policy, with the U.K. accepting thousands of extra refugees.

Failing to holistically or accurately represent experiences of people in wars—from their perspectives—can also lead to biased interpretations, rather than building nuanced public understandings. This leads to audiences being less able to act as informed secondhand witnesses to ongoing injustices.

What does it mean to be a witness in photojournalism?

Check out the Phinker podcast, Frame by Frame, to find out.

Decolonising the Gaze

As media professionals, we can shift cultural understandings. Dr Helen Vatsikopoulos, a journalism lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney, argues “media is crucial in normalising diversity and demolishing the ‘othering’ of difference that divides us.”

But decolonizing the gaze in war photojournalism isn’t just about diversifying who we photograph. It’s a deeper systemic challenge that requires industry transformations in who tells stories. This process involves centring oppressed voices, dismantling colonial views, and promoting self-representation.

It demands a photojournalism by communities, not just of them.

Podcast: Anishinaabe journalist Duncan McCue highlights that industry-wide change is required to decolonise journalism. From the Don’t Call Me Resilient podcast.

For those of us not on the frontlines, our role as viewers is also significant. We need to critically examine power dynamics in the creation and sharing of images. As we consume photographs of war, we must continually ask: whose story is being told, and whose voices are missing?

Supporting and sharing work by war photojournalists who are from the regions they cover is a concrete step toward challenging the colonial and outsider gaze, leading to a more nuanced understanding of global events:

Original image description: @alijadallah66 is another Palestinian photojournalist in Gaza. His work has been recognized internationally as he continues to document the war crimes of the Occupation Forces. Ali has also captured the beauty of Gaza when it’s not actively under attack. You can see some of those moments of joy captured in the second photo, as droves of Palestinians in Gaza enjoy the once-calm beachside of the Mediterranean. The following photos are Gaza now, as it is under attack by Occupation Forces. Protect Gaza’s journalists. Demand a ceasefire now.

Image: On their Instagram, Eyewitness Palestine are highlighting insider perspectives: Palestinian journalists and photographers documenting the war in Gaza. Image by Eyewitness Palestine.

Decolonising the gaze is an ongoing, active journey.

Let’s do our part.