Confronting Photojournalism’s Gender Crisis

Women face Less Pay, Sexism, and Harassment

Trigger warning: this article contains discussions of sexism, gendered harassment, and sexual violence.

The Walkley Awards, Australia’s top media honours, will break new ground in 10 days by exclusively awarding female journalists in the Outstanding Contribution to Journalism category. The move addresses an historical imbalance, with just 7 of the past 30 awards going to women.

“We must do better,” admitted Adele Ferguson, Walkley Foundation Chair.

But awarding women’s outstanding contributions fails to recognise or address industry-wide issues that stop us from contributing equally to begin with, especially as visual storytellers. Fewer opportunities, lower pay, sexist discrimination, and sexual harassment are part of what researchers call a “gender crisis in professional photojournalism.”

A Snapshot of Sexism

There’s no two ways about it: the stats are dire.

Over 80% of photojournalists globally are male, only 9% of Reuters’ image assignments go to women, and Getty don’t have a single female staff photographer worldwide. Female photographers earn 40% less than male peers—despite more female photojournalists holding photography and journalism degrees—and 69% face sexist discrimination at work.

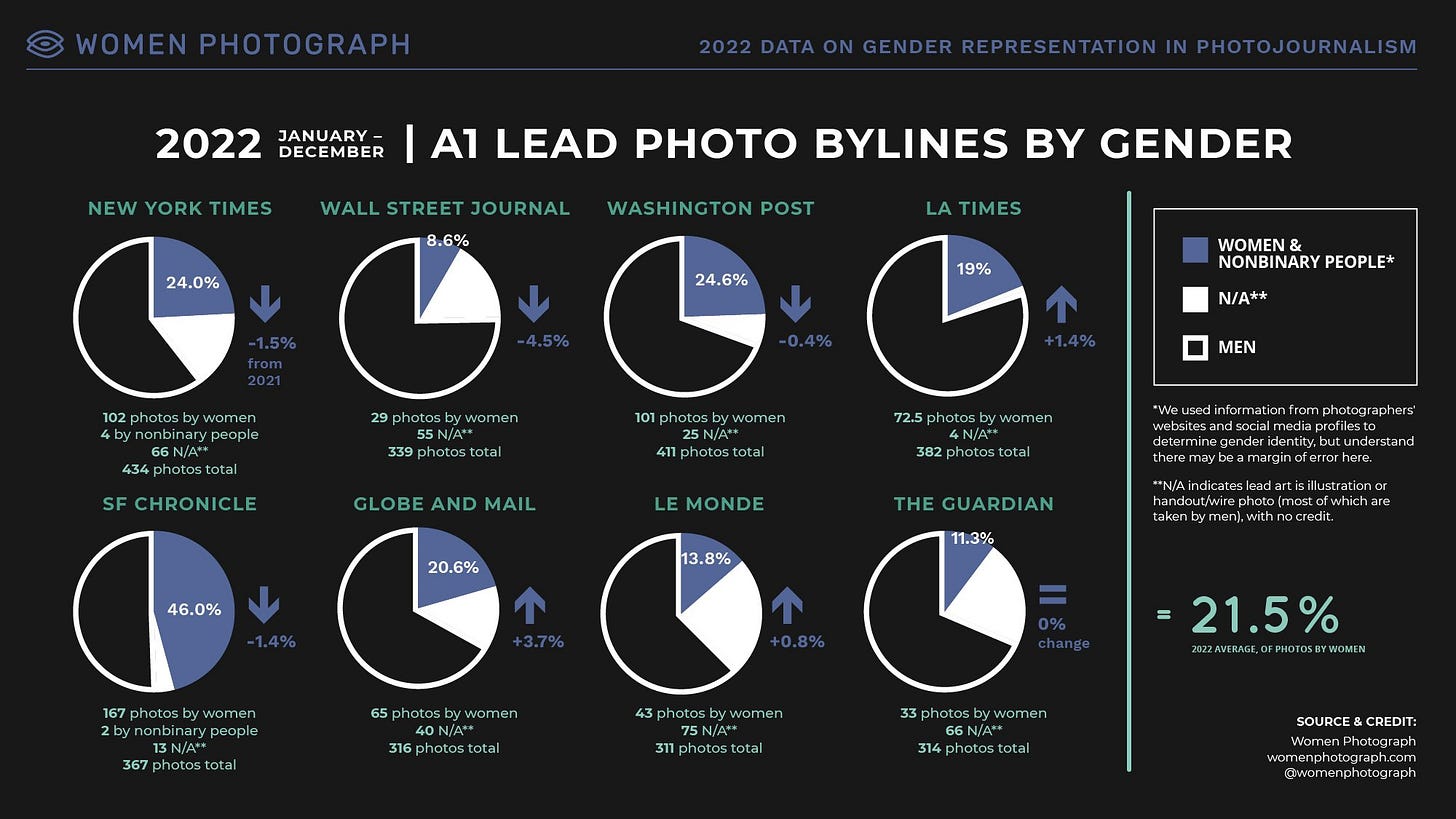

It’s no better in publications. Women Photograph track daily front-page photo bylines in eight global newspapers. In a six-year first, 2022 saw a decline, with just 21.5% of lead photos by women and nonbinary photographers:

Image: Female photojournalists are underrepresented in the industry, including in publications. Image by Women Photograph. Used in accordance with Women Photograph’s terms.

The Walkley example also illustrates a broader trend in professional accolades: only six women have won a Pulitzer for news photography since 1968, and five a World Press Photo of the Year since 1955.

Brand recognition is lacking, too. Just 14 of 109 Canon Europe’s 2021 ambassadors were women. Nikon’s 2019 lineup of 32 photographers had none.

“It’s still a boy’s club,” said photographer Kris Smith in a report into industry gender disparities, and “they won’t bump a man for a woman.”

In the Field? Hello, Harassment

Sandra Potisek, while researching the report, found “every woman photographer I’ve ever spoken to had stories to tell. Men? Not so much.”

Stories about being a female photojournalist often involve harassment and sexual violence. Recent studies show 88% face physical risk at work, and 94% have been harassed by professors, colleagues, camera gear salespeople, or the public.

Video: Like the majority of women in the media, including 94% of photojournalists, Global News reporter Julie Nolin has been harassed at work. Video by Fresh Daily Canada.

Power imbalances make it worse.

In the past five years, journalists have exposed multiple high-profile sexual misconduct cases. Industry veteran and Magnum photographer David Alan Harvey was accused of masturbating on video calls, National Geographic’s Patrick Witty of predatory sexual behaviour, and Antonín Kratochvíl—co-founder of eminent agency VII—of sexually assaulting colleagues.

A Culture of Inequality

These issues are not just statistics.

They’re a reflection of structural inequalities permeating society.

The male-dominated industry, rooted in patriarchal norms, creates a culture where women’s time is undervalued, work undercompensated, and safety compromised. This replicates and reinforces societal gender disparities, where female voices are systematically marginalised.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Video: The discrimination and harassment female photojournalists experience in the media industry is rooted in systemic and structural causes. Video by We Are Man Enough.

Such gender gaps shape visual journalism narratives. Historically, women were discouraged from becoming photojournalists due to biases about gender roles, but patriarchal norms still inform industry ideas about gendered interests and capabilities. Female photojournalists are assigned more lifestyle and soft news stories—while men dominate hard news and high-risk assignments.

It limits women’s career opportunities, too. “I see so many women just miss out on jobs,” said Jaki Jo Hannan, founder of a nonprofit championing female and nonbinary photographers. “Male photographers who get that work go on to get more of it . . . it becomes this perpetual cycle that makes the gap wider.”

What scholars call the “demise of the female gaze” also impacts representation: less than one-third of news images show women. Hiring more women does not guarantee increased female representation. But studies show male photojournalists depict men more often, while women’s representation increases under female editors.

Image: When women producing media are underrepresented, women depicted in media are, too—but addressing the former helps fix the latter. Podcast by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Toward Gender Equality

Female photojournalists have long called for change. The shift in this year’s Walkleys is a start. And while systemic change requires addressing root causes, there are steps we can take now.

Hiring more women, and publishing more of their work, is essential. Equal Lens, ShotByWomen, and Hundred Heroines have rich databases of talented photographers.

Initiatives like Women Photograph, Girl Gaze, and the International Women’s Media Foundation support female photojournalists through grants, workshops, and networking. Supporting them helps women thrive.

Video: Initiatives supporting female photojournalists are helping address the gender crisis—like Women Photograph, whose book ‘What We See’ spotlights work by female and nonbinary photographers. Video by the PBS NewsHour.

Finally, we can amplify women’s voices on socials, challenging algorithmic bias by following and engaging with female photojournalists. Here’s a list of 20 to get you started.

Change grows through our collective efforts, but starts with one person.

Let that person be you.